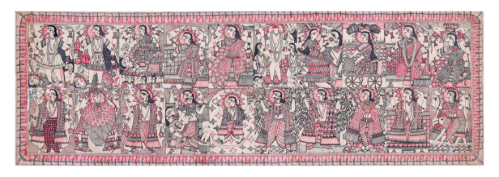

In the intricate, luminous world of Krishnanand Jha’s paintings, the divine does not shout. It gestures. It points. It pulses through ink and space. Among the most remarkable of his works is a wide-format panel of the ten Mahavidyas—the ten manifestations of Shakti, the cosmic feminine force in Hindu tantra—arrayed not in hierarchy, but in rhythmic variation. In this piece, and in several related works, Jha draws not only from the deep well of Mithila tradition but also from his own lineage as the son of a Tantric priest. His goddesses do not float above the world; they are anchored in it, rendered with steady line, deliberate symmetry, and a compositional logic that is as devotional as it is formal. His is a sacred visual language, one that insists the divine can be found not only in myth but in gesture, form, and line.

The Mahavidya panel unfolds like a mantra. Ten goddesses—Kali, Tara, Shodashi (Tripura Sundari), Bhuvaneshvari, Bhairavi, Chhinnamasta, Dhumavati, Bagalamukhi, Matangi, and Kamala—each embodying a distinct aspect of Shakti—hold their ground across the frame, distinct yet composed within a shared visual rhythm. They do not compete for space. Instead, one figure gestures toward the next: a raised finger, a tilted trident, the gentle curve of an arm. The viewer is moved forward not by narrative, but by line. There is no crowding, no chaos, but composed intensity. The background, left mostly unpainted, becomes a kind of charged void. This restraint allows each figure to breathe, while their gestures act as directional cues, a type of graceful pointing, guiding us across the surface like a pilgrimage of sight.

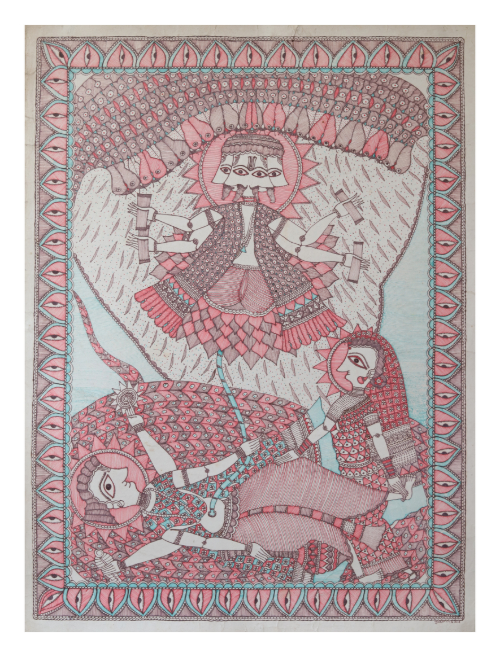

It is within this language of rhythmic linkage and directional gesture that the work of Santosh Kumar Das enters the conversation. A contemporary master of the Mithila tradition, Das builds his compositions not on the momentum of movement but on the equilibrium of stillness. Where Jha’s Mahavidya panel guides the gaze through a sequence of gestures, Das’s Kali—the fierce goddess of time, destruction, and transformation—fixes the viewer in a direct, frontal encounter. The black-bodied goddess stands atop Shiva, six arms evenly arrayed, a yantra anchoring her at the base. Ferocity here is not projected through stride or sweep, but concentrated in an unbroken gaze and symmetrical balancless a procession across space than a meditative holding of it.

Across both Jha’s and Das’s works, color functions as a precise symbolic language rather than mere decoration. Red, black, and white dominate—each charged with layered meaning in Mithila and tantric traditions. Red is energy in its most vital forms: blood, menstrual power, fire, and passion. Black is the void, night, ink, and dissolution, the absorber of all form. White is not emptiness but stillness, transcendence, and spiritual clarity. Neither artist floods the surface with these colors; instead, they place them with deliberate restraint—on a tongue, a halo, a weapon tip—so that each instance pulses with meaning.

If color is the pulse of these works, gesture is their voice. In Jha’s paintings, hands are never passive. A single raised finger may carry as much weight as a weapon or a severed head. These are mudras—symbolic hand gestures used in Hindu and Buddhist ritual—translated into pictorial form. They guide, command, bless, or withhold. The pointed finger, in particular, recurs across his oeuvre, a visual mantra that directs the viewer’s gaze from one figure to the next. This “pointed grace” shapes the narrative flow of the Mahavidya panel and channels the fierce equilibrium of Chhinnamasta.

In Das’s works, gesture operates differently. Arms and hands are often held in perfect symmetry, theirmirroring reinforcing the image’s stillness. The goddess’s hands do not guide the viewer outward but hold the energy within the frame, like the balanced arms of a yantra. Both approaches reveal a theology of Shakti: in Jha, divine force moves through directional flow; in Das, it emanates from the center, unwavering and eternal.

In motion and in stillness, both artists affirm the same truth: the goddess is the axis of the world. Whether she guides us across the painted surface or meets us in perfect frontality, Shakti’s presence remains unshaken—eternal, commanding, and complete.

Exhibitioin continues till September 21, 2025

Monday closed, 11am to 7pm